Hello, friends. Welcome to our new subscribers. (Both of y’all.)

My family spent the Labor Day weekend visiting family on the east coast. It was absolutely lovely in the North Carolina mountains.

I also saw a lot more cable news than I’m used to last weekend. If you’re worried that CNN maybe didn’t spend an entire morning covering mud at Burning Man and how popular Trump is with Trump voters, rest easy. These were the most important things happening in the world, and they got the attention they deserved.

Sure, cable TV is bad, but at least we have the internet, right?

Xitter is getting xittier and xittier, with Elon now blaming the ADL, an organization that exposes anti-semitism and racism, for his company’s advertising losses. And not blaming, you know, Xitter placing advertising on Hitler fan accounts and then giving the Nazis a cut of the revenue. Why would the Jews do this?

Xitter also announced the beta launch of a hiring app, which is awesome if you need some unemployed racists to help with your misogyny startup. (BTW, Facebook tried to make Jobs on Facebook viable for years, with 20 times as many users as Xitter, before shutting it down earlier this year. But it might work for us.)

As the “X app” becomes ever cultier, we’re seeing the rise of a flavor of humanity that defies all rational understanding: The dude aroused by the thought of the World’s Richest Man successfully consolidating and taking a cut of all their economic and communication activities. Control me, daddy.

Smoking the past

My home office is like the world’s ugliest museum of ‘90s-’00s hipsterism. It’s just a terrible mess of haphazardly-hung indie show posters, outsider art, and ugly kitsch. Plus piles and cabinets full of detritus.

We’ve lived in our family home for over 12 years now, which is long enough to have forgotten about old “treasures” deep in its dustiest nooks. I recently found a box that was full of ancient magazines, many of them sports titles from the 1980s.

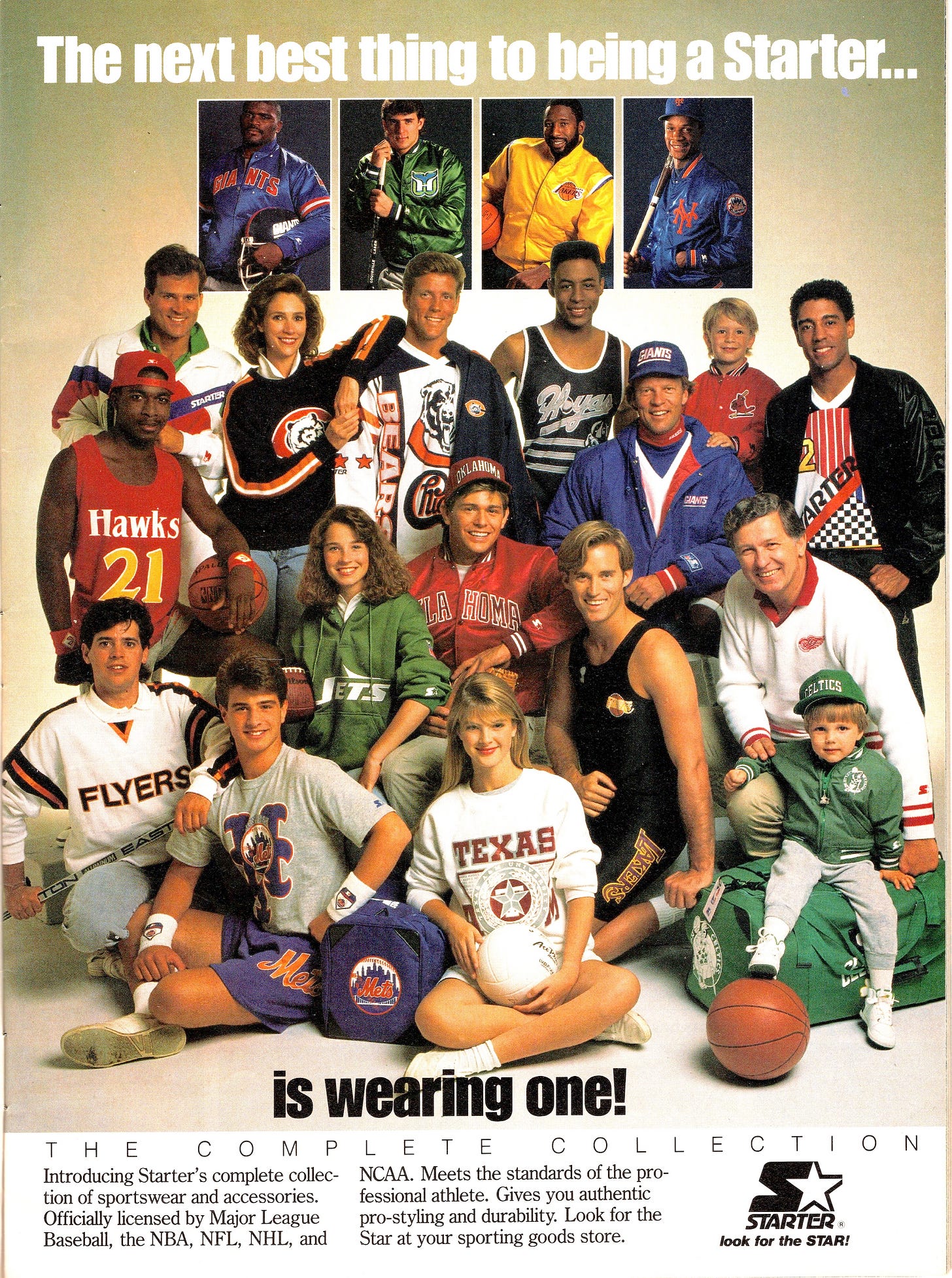

So last week, I spent about two hours with the 1989 Inside Sports basketball preview issue. About 10 of those minutes were spent staring at this ad.

Imagine the energy that went into this shoot, which predates Photoshop. The casting, the choices, the micro-positioning of every finger and hair — this must have been excruciating for everyone involved. I bet the bro in the Mets gear still has back pain from sitting like that for five hours. But he earned his $114 before taxes, and this was the medium that mattered in 1989.

Magazines have now been irrelevant for so long, it’s almost hard to remember just how glorious and important they used to be. Back before internet advertising killed print, the average person spent hours each week reading magazines. This habit crossed generations, social classes, and urban/rural divides. You could glance around a crowded bus, the line at the bank, the dentist’s waiting room: If people had idle time, they were probably flipping through a magazine.

If you revisit any magazine from 1980s or earlier, you’ll see a number of anachronisms. One of the most obvious is the prevalence of ads for cigarettes.

Cigarettes are a nearly undifferentiated commodity, so tobacco companies tried to play around with the form factors to sell them. Some were long, some were slim, some were unfiltered, some were brown, some were “organic” (lol), some were “light” (LOLLLLLL). Some were targeted at blue collar men, others for African-Americans, others for aspirational career women, others for young health-conscious Xers. But all were just basically the same drug sticks that gave people the same diseases. So brand really mattered.

For the better part of 50 years, tobacco was the lifeblood of American media. If you opened almost any magazine, browsed the billboards over the freeway, or looked at almost any solid object between the ground and outer space, you’d see an ad for smokes.

The pilot episode of Mad Men used cigarettes to introduce how advertising works. The first account we ever see Don Draper win is Lucky Strike, whose executives are exasperated by new restrictions on making health claims. After some deep thinking and market research at the bar, Don delivers the winning pitch: “It’s toasted.”

Tobacco exec: But everybody else’s tobacco is toasted.

Don: No, everybody else’s tobacco is poisonous. Lucky Strikes’ is toasted.

This pivotal early scene introduces how advertising not only reflects but shapes American postwar culture. And since Don is a con man with a phony identity, it demonstrates how Americans can be whatever they want by pretending, confidently. Like cigarettes can.

Advertising is generally protected by the First Amendment, but as we know free speech isn’t without its limits. For tobacco companies, new regulations from the Federal Trade Commission meant no more ads with authoritative men in white lab coats saying stuff like, “Ladies, medical research says: Vantage 100s will keep your waist slim. So your husband won’t cheat on you again.”

A couple decades later, Joe Camel got a lot of attention from Congress and the media. He was somehow both designed to attract kids and also clearly a flaccid penis and balls. If Joe were still around, even liberals would call him “groomer.” Here’s an ad from that same issue of Inside Sports. (Nine of the issue’s 84 pages are cigarette ads.)

Eventually, Deep State communists forced tobacco companies to affix minuscule, ineffectual warnings to its ads and packaging, and then by the 1990s they made it really hard for them to advertise at all.

Today you won’t see tobacco ads on TV, radio, or billboards. You won’t see YouTube video ads or TikTok influencers promoting Marlboro or American Spirits. The Winston Cup is no more.

And those restrictions are nothing compared to what you see in other countries, where advertising is almost completely illegal, and they print graphic photos of diseased bodies right on the packs.

These marketing restrictions have had tremendous impact. People smoke a lot less than they used to. The old-heads might remember smoking sections in restaurants and airplanes, candy cigarettes in Halloween bags, and coming home from the bar stinking like a damn forest fire. (I remember when I first moved to California, shortly after they’d banned smoking in bars, I woke up after a night out and struggled to remember if I’d had fun. My primary sensory cue, the cig stink, was missing.)

The restrictions on tobacco advertising are also a model for how government regulation can drive strong and positive health outcomes. At a time of declining public health and life expectancy in the US (and, uh, everywhere else), this is a rare win.

But we need to be clear exactly what we’re talking about here: The federal government, with cooperation from state governments and the legal system, cracked down on a multibillion-dollar interstate operation that employed hundreds of thousands of Americans. In America, this is very unexpected!

But we’re going to need more of it.

Commercial censorship saves lives

In the decades following NAFTA, obesity exploded in Mexico, from 10% of the population to over 35%. Mexico’s obesity stats even leapfrogged the USA’s, which seemed unthinkable.

The causes of booming obesity rates around the entire world are many and complicated, but obviously the transformation of diets from local agricultural products to imported ultraprocessed foods have a lot to do with it.

Mexico, like many developing countries, in less than two generations swung from “people don’t have enough calories to maintain their health” to “people have too many calories, and they’re the bad kind.” And this has cost theirs and other nations dearly, with an explosion of serious illnesses that are commerciogenic, meaning caused by the profit interests of industry. This is a word that gained prominence in the 1970s, when Nestle’s promotion of baby formula in the developing world led to widespread child malnutrition, inspiring a movement to boycott Nestle.

To respond to its obesity crisis, in the mid-’10s the Mexican government started regulating junk food. Similar to tobacco, this regulation includes higher taxes, warning labels, and banning cartoon characters. These requirements have now expanded throughout Central and South America.

As a result, global food companies now produce special packaging for those markets. For example, here’s Cap’n Crunch without the Cap’n, and with a number of warnings that don’t require a shopper to read and understand the nutritional facts, or conduct calculations in the supermarket aisle. I took this photo in Mexico last winter.

It’s unlikely that anyone believed that Cap’n Crunch was a healthy food product. But here’s the thing with the labels: they’re not just about warning that this product is bad for you. They also warn about an entire category. Nearly every product in the cereal aisle bears these excess calories / sugar / salt warnings. If you read the nutritional labels on cereals in the USA (and do some calculations), even the “healthy” ones are more than 25% sugar by weight, and the junk ones can get closer to 50%, which makes them more like dessert than breakfast. (In fact, sugary cereals make for an excellent desserts!)

In Chile, this same style of black octagonal warning labels is driving change.

In focus groups, parents have reported that their children tell them off when they reach for sugary, fatty or salty options in the supermarket, and even "pester" them to go for the healthier choices. The parents think this is down to what the children have been taught about nutrition in school over the past years.

We’ve reached a growing scientific consensus that global reliance on cheap, nonperishable, ultraprocessed foods are responsible for all manner of physical and even mental illness. We’re not just talking about Cap’n Crunch, Sour Patch Kids, and Mountain Dew here. We’re talking about bread, mac and cheese, juices, yogurts, and other modern dietary staples, none of which are what they used to be.

I’m not trying to be all organic-whole-non-GMO woowoo here. Our house is full of this stuff, too, and while I think we eat healthier than most families, that probably means we get half our calories from ultraprocessed foods instead of all of them. Eating real food is an expensive luxury.

Ultraprocessed foods are engineered to drive addiction. They’re unapologetically marketed to children and presented in colorful packaging meant to inspire positive emotions among the adults purchasing them.

Jeez, this all seems so familiar.

America never banned tobacco. You can still buy smokes in every county. And we never will — and shouldn’t! — ban Dr. Pepper, instant ramen, and Count Chocula. Even the hint of a federal health recommendation around alcohol consumption recently inspired a particularly stupid Ted Cruz stunt that’s a preview of “they want to take your beer and cookies away.”

Companies that make unhealthy products use a common word when they’re under fire: choice. When you hear about “consumer choices,” you’re usually hearing companies that make addictive or unhealthy products attempting to reframe public health regulations as a form of totalitarianism. They don’t want to control us; they want to control you.

Search for “consumer choice,” and you’ll find all manner of astroturf organizations, some of them one-offs to fight regulatory legislation, and others more enduring. The graphic above is from Consumer Choice Center, which describes itself as a “grassroots movement,” while also disclaiming:

In the past, we have received funding from multiple industries such as energy, fast moving consumer goods, nicotine, alcohol, airlines, agriculture, manufacturing, digital, healthcare, chemicals, banking, cryptocurrencies, and fin-tech.

The idea of “choice” is incredibly naive and false. Companies have unprecedented power to exploit our common psychological vulnerabilities. Smokers aren’t choosing to light up their 11th cigarette of the day, after all. The only really “healthy choices” in the supermarket are also the most perishable and expensive. Most people’s choices are false. You literally pick your poison.

Let’s conclude with this: the industrialized Western diet is absolute shit. The human palate evolved over millennia of hunter-gatherer societies to increase our odds of survival, and it bears no relation to the food systems that mass-produce edible substances. What we eat is increasingly formulated in labs by food scientists to exploit these disparities, so we find ourselves craving flavors and textures that our bodies perceive as “nutrition,” even as they provide nothing of the sort.

At the same time, these companies will dump a bunch of vitamins or boast “3g of dietary fiber” on the box, so they can fool our brains along with our bodies. Companies have become so good at fooling people, that food companies have exported the industrialized Western diet to all corners of the world. Just like they did with cigarettes.

Many of the commercial decisions we’re making in our lives seem like choices, but they’re really scams. And until people understand they’re scams, they’re not really making choices at all. And that’s why we should have warning labels on everything.